I. Introduction

The scope of geographical indications (GIs) disciplines generally entails the following: geographical indication, indication of source and appellation of origin. In the first instance, by definition a geographical indication, which is much broader and an inclusive term, is generally a notice declaring a specific geographical area as the origin of a product.[1] In the second instance, an appellation of origin may entail three designations: the geographical name of a country; region; and a specific place representing a product’s origin and characteristic qualities. All these three designations are collectively exclusive or essentially akin to a geographical environment.[2] In the third and last instance, an indication of source refers to any expression or sign used to signify that a product or service derives its origin in a country, region or specific place.[3]

In view of the scope of GIs, its importance to the African continent cannot be overemphasized. The miscellany of Africa’s geographic make up and the diversity of its environment and products renders the continent pregnant with endless possibilities to derive maximum value from its geographical indications. In this context, phase two negotiations of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents a window of opportunity to turn these possibilities into reality. The account below discusses the importance of GIs in the context of AfCFTA phase two negotiations.

II. Rationale and Overview of GIs Treatment in Trade Negotiations

Areté[4] and Teuber[5] recognize that the protection of products under GIs fosters quality production, growth and better distribution of profits and thus results in higher economic gains. Consequently in the context of the African continent, GI protection has the potential to benefit local communities through amongst others encouraging preservation of biodiversity, local know-how and natural resources. From the perspective of Mengistie[6] and Sautier et al,[7] GIs protection can provide adequate protection at the international level.

GIs have been subject to negotiations at multilateral, bilateral and plurilateral levels. At the multilateral level (i.e. World Trade Organization (WTO)), substantive GIs negotiations were last held in 2014 albeit without notable differences registered among the members.[8] The scope of these negotiations include: proposals for extension of higher level of protection[9] accorded to Wines and Spirits under Article 23 of WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement to other products;[10] and a requirement for patent applicants to disclose the origin of genetic resources, any related traditional knowledge utilized in their respective inventions and provision of evidence of prior consent as well as fair and equitable benefit sharing.

In respect of the above multilateral WTO negotiations, the African countries are proponents of the following positions:[11]

- Extension of the protection of Article 23 of the TRIPS Agreement to geographical indications for all products, including the extension of the Register. A number of products from African countries informed this position for consideration as candidates for GI protection. These may include Pink rice from Amparafaravola, Madagascar; Imraguen women’s mullet bottarga from Mauritania; Tete goat meat from Mozambique; and Fruits from Lower-Casamance, Senegal.

- Amendment of the TRIPS Agreement to include a mandatory requirement for the disclosure of the country providing/source of genetic resources, and/or associated traditional knowledge for which a definition will be agreed, in patent applications. Patent applications will not be processed without completion of the disclosure requirement.

- Establishment of a register open to geographical indications for wines and spirits protected by any of the WTO Members as per TRIPS.

There is therefore no doubt that African countries are the proponents of a wider scope of GIs protection. Key to their position is the notion that expanded scope of protection is inter alia considered a corollary to promotion of trade in value added goods and liberalization of agricultural trade. However, to date, consensus among the WTO members remains elusive with opponents such as the United States and Australia arguing amongst others that there may be additional costs, including consumer confusion and the heightened potential for disputes.[12] Consequently, progress on addressing the interests of most African countries in the area of GIs appears to be remote in the short and medium term. This notwithstanding, progress in other non-WTO negotiations in the area of GIs has been registered.

Across the world, more than 25 GIs and GI-related agreements in force are configured in various formats. These include agreements on GIs concerning wines, spirits and both wines and spirits; agreements on GIs concerning agricultural products and foodstuffs; and agreements on GIs specific to agricultural products and foodstuffs, wines and spirits.[13] Additionally, the GIs found in free trade agreements (FTAs) and other agreements cover non-exhaustive elements such as the scope of protection, criteria for designations of products, labeling of protected products, in-built negotiations, specifically identified GIs, GI shortlists and opposition procedures, protected GIs and coverage of the coexistence between trademarks and GIs.[14]

Notably, South Africa and Morocco are the only African countries party to GIs Agreements. As for ongoing negotiations, there are seven agreements under negotiations covering GIs. These include a few African countries namely Morocco and those from the East African Community.[15] Nevertheless, in juxtaposition to the rationale for GIs protection and the support for expansion of scope of protection of GIs at WTO level, African countries are yet to adopt substantive GIs agreements or disciplines that confer GIs protection foreseen in their WTO proposals.

III. Characterization of the African GIs Environment

The GIs environment in the African continent is generally characterized by treaty-based obligations as well as best endeavor commitments. The regulatory framework within which GIs subsist in Africa is considered hereunder.

The African Intellectual Property Organisation (OAPI) Bangui Agreement protects GIs through a sui generis system as a distinct regime relative to the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) Banjul Protocol.[16] The Banjul Protocol provides that GIs can be registered as collective or certification marks. Moreover, applicants may file a single application with the contracting states or the ARIPO Office, and designate states where protection is sought. At treaty level, it is therefore clear that African countries follow divergent approaches to GIs one being a sui generis system[17] followed by OAPI as opposed to ARIPO’s approach.

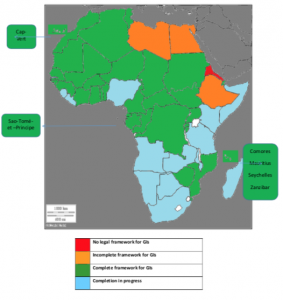

At the African Union (AU) level, a seminal Continental Strategy for GIs in Africa (2018 – 2023) was adopted in 2017. The strategy among others aims at developing rural areas in Africa, preserving African heritage and tradition as well as helping farmers and producers in the continent to gain from value addition and the use of protected quality products. There is no doubt that agriculture related GIs are important to the African continent and this is consistent with the position of most African countries at the WTO level. Among six outcomes of the strategy one perceptibly relates to the AfCFTA, namely, the creation of an enabling legal and institutional framework for the protection of GIs at national and regional levels.[18] It further pertains to the overall status of individual African countries’ legal frameworks in relation to GIs as depicted in Figure 1 below. While the strategy is welcome, it leaves the pursuit of GIs protection at the discretion of individual countries except for the case where AU members have created a legal and institutional framework under the AfCFTA.

To give a picture of GIs status at the country level, three African countries stand out in respect of the regulatory approach to GIs. Kenya, with the support of the Swiss Institute of Intellectual Property, developed a draft law on GIs, albeit not yet in force.[19] Morocco provides GIs protection through a sui generis system in which the law 25-06 established protection for products in addition to wines. The protection is also through appellations of origin and agricultural labels. Lastly, in South Africa the law on trademarks protects geographic indications. All this highlights the notion that at the individual country level, legal regimes on GIs in Africa are heterogeneous.

In view of the strategy mentioned above, African countries undoubtedly have a keen interest in GIs protection. Nevertheless, a lot more work is certainly needed to provide a context-based homogeneous GIs legal and institutional framework as well as other associated procedural aspects. These will give effect to a nuanced appropriation of benefits from GIs protection by countries and communities across the African continent. Given the short life span of the strategy, the AfCFTA provides a rare window of opportunity with respect to creating a legally binding framework across the continent.

Figure 1 below depicts a picture of existing GIs legal frameworks under the auspices of regional intellectual property (IP) bodies and the WTO. Drawing from this depiction, the AU strategy on GIs concludes that national regulatory frameworks of African countries on GIs are still evolving. It recognizes some deficits such as instances where certain African countries have not enacted secondary legislation to give effect to their obligations, as well as the existence of discrepancies in the definition of GIs and the scope of protection and legal frameworks, which generally do not reflect African interests.

The above cited deficits and differences in legal regimes, which extend to areas such as registration processes, the role of states and lack of provisions regarding transborder GIs characterize the environment within which GI regimes operate in Africa.[20] Collectively, these deficits and differences are an open invitation to AfCFTA negotiators to seize phase two negotiations as an opportunity to create a GIs regime that addresses the interests of the continent and that is operationally feasible.

Figure 1: Degree of Achievement of the Legal Framework of GIs

Source: African Union 2020

Source: African Union 2020

In a nutshell, the GIs regulatory framework in Africa is generally fractured and heterogeneous, with most countries lacking the capacity to operationalize their obligations. Given the fractured GIs regulatory environment in the African continent and the fact that at the multilateral level there are no short to medium term prospects for the adoption of favorable new rules, phase II negotiations of the AfCFTA presents an opportune moment to introduce a cohesive continental approach to GIs. It further presents an opportunity to AfCFTA negotiating partners to define the scope of a beneficial GIs regulatory regime as well as the best ways to operationalize resulting commitments.

Challenges

The primary challenge that will confront the AfCFTA negotiating countries will be to come up with a GI system that is contextual to the market characteristics, anthropological and topographical realities of African countries. Consequently, a comprehensive definition and treatment of potential GIs in relation to the above cited realities would be needed. As an example of topographical and anthropological consequences of a GI system in Africa, in 2010 the first collective mark was registered in Kenya for the Masaai community and an attendant regulation providing protection over the use of collective marks in products was promulgated.[21] To the extent that this collective mark amounts to a geographical mark and thus topographically significant, it may be argued that the Masaai communities in neighboring countries may consider themselves equally eligible for such protection, which at present is not offered by their countries. It is these kinds of cases that are bound to arise and hence the primary focus of African countries should among others be to reconcile the need for GIs and the peculiarities of African GIs topographical and anthropological realities.

The fractured and heterogeneous GIs regulatory framework within the African continent implies that AfCFTA negotiating countries will be confronted with a mammoth task of having to set a level of ambition that is agreeable to all countries. As an example, a reconciliation of ARIPO and OAPI GI legal frameworks as well as those adopted by individual countries including in their respective FTAs will bear heavily on the chances of success in the negotiations on GIs. The International Trade Centre (ITC) established that in Sub-Saharan Africa, systems exist, albeit essentially not being utilized due to, among others, confusing regulations, high costs and bureaucratic hurdles.[22] Balancing these challenges and ensuring that a meaningful GIs regime is developed will be key.

There are numerous challenges at the technical level that negotiators must contend with in ongoing AfCFTA negotiations. These may include establishing the legal basis for the protection of GIs; the definition of protected GIs; the scope of participation in the GI system and its consequent legal effect;[23] the nature and reliability of GI notifications and the integrity of information provided; whether or not to specify the product for which GIs protection is sought; the date of GI protection; automaticity of the registration system; and the reservation system.

Operationalisation of the GIs system will be the main test the success or failure of any given treaty on GIs. AfCFTA negotiating countries will have to contend with setting up a fit for purpose and efficient institutional framework for the operationalization of an agreement on GIs. Nevertheless, according to ITC, in many developing countries, the GIs systems are often at an embryonic stage with governments having by very limited capacity to protect their own or foreign GIs. [24] Hence, capacity constraints represent the single most important issue that must be addressed.

Best Practices

Developing a GIs system under the auspices of the AfCFTA should take into account international best practices given that the AfCFTA has the potential to foster international recognition of African GIs and provide protection that is not available under international conventions.

At the mechanical level, one of the approaches worth considering is drawing up lists of specific GIs to be offered protection under free trade agreements (FTAs). By implication, prior assessment of potential candidates for protection under the GIs system must be carried out. This will serve to, inter alia, ensure effective protection against claims such as on names considered as generic; trademark misappropriation; and unauthorized use of listed GIs.[25]

It is notable that a common practice in the treatment of GIs in FTAs is to include them among the intellectual property or market access provisions. This notwithstanding, looking at the developed countries with respect to GIs, the US and EU approaches can serve as an important reference to the AfCFTA negotiating countries. As an example, the United States approach to GIs focuses on brand development or marketing. In the case of Europe, the approach to GIs is eclectic focusing on community development including branding and marketing.[26] In this context, a market-based approach opens up beneficiation from the GIs system to third countries, while in practice the community development approach tends to limit the extent of market openness to third party GIs registrations.[27] AfCFTA negotiators must therefore take a cue from these advanced systems with a view to developing a system that is customized to African peculiarities and realities.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations for the AfCFTA Negotiations on GIs

The take up of GIs in AfCFTA negotiations should contribute towards economic and social goals and support sustainable development. Initiatives on GIs at the continental level should address interests and market realities of African countries over 90% of whose economies are represented by small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The recognition that globalization and new technologies may erode the value of potential GIs from the continent as well as the fact that the reputation and value of GI products may lead to imitations and free-riders should inform any initiative adopted on continental GIs.[28] This makes the role of public policies, including at the continental level, extremely important. In particular, the provision of a sound legal framework[29] at the continental level will be key.

Taking a cue from section III above, the GIs legal framework at the continental level should reconcile fragmented legal regimes of African countries into a cohesive system of rules that will address value eroding differences among countries’ approaches to GIs. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the creation of a GIs legal framework by public institutions should focus on four key areas, namely identification, qualification, remuneration and reproduction as highlighted in Figure 2 below. [30] Given the observations by the AU GIs strategy discussed above there is no doubt that the said legal framework should be considered at the continental level. This approach will ensure comprehensive coverage of GIs while also creating rules that are unique to the circumstances and interests of African countries. Similarly, as highlighted in the previous section, there is a deficiency of rules at the multilateral level in the area of GIs. As such, African countries consider the prompt review and updating of WTO rules crucially important to address their interests.

The creation of rules unique to the African continent under the AfCFTA will likely expedite the exploitation of benefits arising from GIs protection and avert delays occasioned by the gridlock in WTO negotiations on GIs. This may also turn the tide in favor of African countries and address a weakness identified by the AU’s GIs strategy, namely that the GI legal frameworks of most African countries do not reflect African interests. Proactive rule-making in areas where there is no consensus yet at the multilateral level will guarantee that African countries are not just rule takers but also rule makers.

While considering international best practices, under the AfCFTA phase two negotiations, African countries can create rules that are unique to the African economic environment and products as well as being responsive to its diverse geography, culture and geographical make up.

Figure 2: The Origin – Linked Virtuous Circle

Source: FAO 2010

Source: FAO 2010

At the technical level, as part of the overall intellectual property negotiations, there are a number of issues that the AfCFTA negotiations on GIs must consider. As a rule of thumb, it must be ensured that the GIs disciplines ultimately adopted address the interests of all the AfCFTA contracting parties. However, the current African GIs legal framework has been described by the AU’s GIs strategy as falling short of meeting the interests of African countries. In this regard, a number of substantive issues must be brought into a sharp focus in the AfCFTA negotiations.

Key issues for consideration during the ongoing AfCFTA negotiation include:

- Assessment of the characteristics of the African GIs market and determination of the best suited GIs system, including the cost and efficiency of the system.

- Whether the treatment of GIs will be part of the existing intellectual property regime, a standalone regime or a mixture of both.

- The merits or demerits of following a GIs regime grounded on a sui generis approach versus other approaches

- The nature of the desired agreement, its basis, purpose and structure, the degree of regional linkages, ownership, conditions for use, transferability, type and degree of protection, maintenance and duration of protection, means of enforcement related mechanism and revocation and cancellation.

- The balance of rights and obligations as well as the distribution of benefits among contracting parties relative to the GIs protection regime. This is an important area given the shared traditions and culture among African countries and the nature of African societies and communities transcending borders in relation to GIs.

- Protectable subject matter is one area that is core to what can or cannot be protected.

- The treatment of blended products and whether they would qualify as GIs as well as the treatment of non-place names or non-geographical names as an important area of consideration.

- The treatment of collective and certification marks, appellation of origin and the relationship of origin and quality.

- The relationship between GIs protection and beneficiary producers among others in the context of marketing and the provision of legal security necessary to incentivize investment and facilitate export decisions.

- The impact of GIs on third country markets in which producers using GIs are not resident but have their products potentially or actually traded and marketed.

- Other issues such as the relationship between trademarks and GIs with respect to existing trademark rights in the products affected vis a vis possible negative implications of entry into the AfCFTA’s GIs legal regime on producers and products in the market prior such entry into force.

- Reconciliation of the fact that a GI is not only a business asset in a market context, but also a public and cultural asset and thus the need for consideration of how to balance private rights and public interests.

References

- African Group and ACP Group et al (2008) Draft Modalities for TRIPS Related Issues https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S006.aspx?Query=(%20@Symbol=%20tn/c/w/52*)&Language=ENGLISH&Context=FomerScriptedSearch&languageUIChanged=true#

- African Union (2020) Continental Strategy for Geographical Indications in Africa 2018-2018 https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36127-doc-au_gis_continental_strategy_enng_with-cover-1.pdf

- Areté. (2013). Study on assessing the added value of PDO/PGI products. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/external-studies/added-value-pdo-pgi_en.htm

- ARIPO (2019) Banjul Protocol on Marks https://www.aripo.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Banjul-Protocol-2019.pdf.pdf

- Blakeney M et al (2012) Extending the Protection of Geographical Indications: Case Studies of Agricultural Products in Africa. Routledge, NY

- Damary P et al (2017) Training Manual on Linking people for quality products: Sustainable interprofessional bodies for geographical indications and origin-linked products, FAO and REDD, Rome http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7060e.pdf

- European Parliament (2014) Economic Partnership Agreement Between the East African Community Partner States, on the One Part, and the European Union and its Member States

Of The Other Part https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2015/october/tradoc_153845.pdf - 2010. Linking people, places and products. A guide for promoting quality linked to geographical origin and sustainable geographical indications, by E. Vandecandelaere, F. Arfini, G. Belletti & A. Marescotti. Second ed. Produced in collaboration with SINER-GI. Rome.

- ITC (2009) Guide to Geographical Indications Linking Products and their Origins https://www.origin-gi.com/images/stories/PDFs/English/E-Library/geographical_indications.pdf

- Kenya (200) Draft Geographic Indications Bill 2007 https://www.origin-gi.com/images/stories/PDFs/English/Your_GI_KIt/bill_geo_indications2007.pdf

- Marette, Stéphan, Roxanne Clemens and Bruce A. Babcock (2007) The Recent International and Regulatory Decisions about Geographical Indications. MATRIC Working Paper 07-MWP. Midwest Agribusiness Trade Research and Information Center: Ames, Iowa.

- Mengistie, G. (2012). Ethiopia: Fine Coffee. In M. Blakeney, T. Coulet, G. Mengistie, and M. T. Mahop (Eds.), Extending the protection of Geographical Indication. Abingdon: Earthscan.

- Organisation for an International Geographical Indications Network (origin) (2020) Agreements in Force (Ratified or Provisionally Applied) https://www.origin-gi.com/images/stories/PDFs/English/Bilaterals/20200317_AGREEMENTS_IN_FORCE_RATIFIED_OR_PROVISIONNALY_APPLIED_Chronological_order.pdf

- Organisation for an International Geographical Indications Network (origin) (2020) (Completed Negotiations (but agreement not yet in force) https://www.origin-gi.com/images/stories/PDFs/English/Bilaterals/20200317_Agreements_not_ratified.pdf

- Sautier, D., Biénabe, E., and Cerdan, C. (2011). Geographical indications in developing countries. In E. Barham and B. Sylvander (Eds.), Labels of origin for food: local development, global recognition (pp. 138–153). Wallingford: CABI.

- Teuber, R. (2010). Geographical Indications of Origin as a Tool of Product Differentiation: The Case of Coffee. Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing, 22(3–4): 277–298.

- WTO (2020) Geographic Indications https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/gi_e.htm

- WTO (2014) Members prepare for 200-day push on GI register portion of post-Bali programme https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news14_e/trip_12dec14_e.htm

- WTO TRIPS Agreements 1995

- WTO (2007) Side-By-Side Presentation of Proposals: Note by the Secretariat Addendum – TN/IP/W/12/Add.1 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/ta_docs_e/5_1_tnipw12add1_e.pdf

[1] Geographical indications generally include place names used to indicate the source and identify, origin and quality, reputation or other characteristics of products such as for example, “Champagne”, “Tequila”. WTO (2020) Geographic Indications

[2] This may include natural or human factors or both such as in the case of Champagne.

[3] Damary et al (2017) TRAINING MANUAL on Linking people for quality products Sustainable interprofessional bodies for geographical indications and origin-linked product

[4] Areté. (2013). Study on assessing the added value of PDO/PGI products. Accessed on 23 April 2020

[5] Teuber, R. (2010). Geographical Indications of Origin as a Tool of Product Differentiation: The Case of Coffee. Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing, 22(3–4):277–298.

[6] Mengistie, G. (2012). Ethiopia: Fine Coffee. In M. Blakeney, T. Coulet, G. Mengistie, and M. T. Mahop (Eds.), Extending the protection of Geographical Indication

[7] Sautier, D., Biénabe, E., and Cerdan, C. (2011). Geographical indications in developing countries.

[8] WTO (2014) Members prepare for 200-day push on GI register portion of post-Bali programme

[9] TRIPS Agreements Article 22 defines the standard level of protection of all products covered therein while Article 23 provides for a higher level of protection specific to GIs for wines and spirits. The negotiations concern an interest on the part of some WTO member to expand the high level of under Article 23 to other products.

[10] These negotiations seek to create a multilateral system for notification and registration of GIs for wines and spirits. These negotiations have been stalled since 2011.

[11] African Group and ACP Group et al (2008) DRAFT MODALITIES FOR TRIPS RELATED ISSUES

[12] WTO (2007) SIDE-BY-SIDE PRESENTATION OF PROPOSALS Note by the Secretariat Addendum – TN/IP/W/12/Add.1

[13] Organisation for an International Geographical Indications Network (origin) (2020) Agreements in Force (Ratified or Provisionally Applied)

[14] Organisation for an International Geographical Indications Network (origin) (2020) (Completed Negotiations but agreement not yet in force)

[15] EU – EAC Economic Partnership Agreement’ Article 74 recognizes the importance of GIs and parties commit to identify, recognize and protect them albeit this has not yet been done. It provides that “1. The Parties recognise the importance of geographical indications for sustainable agriculture and rural development. 2. The Parties agree to cooperate in the identification, recognition and registration of products that could benefit from protection as geographical indications and any other action aimed at achieving protection for identified products. “

[16] Parties to the Banjul Protocol are Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

[17] The sui generis system concerns laws specifically aimed at protecting geographical indications

[18] African Union (2020) Continental Strategy for Geographical Indications in Africa 2018-2023

[19]Kenya (200) Draft Geographic Indications Bill 2007

[20] African Union (2020) Continental Strategy for Geographical Indications in Africa 2018-2018 https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36127-doc-au_gis_continental_strategy_enng_with-cover-1.pdf at 48

[21] Blakeney M et al (2012) Extending the Protection of Geographical Indications: Case Studies of Agricultural Products in Africa. at 218

[22] ITC (2009)GUIDE TO GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS LINKING PRODUCTS AND THEIR ORIGINS at 51

[23] This is an important issue given the possibility that not all AU Members may ratify all AfCFTA instruments or during the course of negotiations some State Parties may seek exemptions from taking some commitments. There may also be denial of protection of GIs considered contentious between and among State Parties, which may, among others, claim rights over GIs notified by other State Parties. This may perhaps be due to products whose geographic origin is attributable to communities living across two or more borders. The unique geographic set up of African borders is one area that may require a bespoke approach that may generally much more pronounced to the African continent.

[24] ITC at 51 Supra Note 24

[25] Sylvander and Allaire 2007

[26] ITC (2009) GUIDE TO GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS LINKING PRODUCTS AND THEIR at 56

[27] Marette, Stéphan, Roxanne Clemens and Bruce A. Babcock. 2007. The Recent International and Regulatory Decisions about Geographical Indications.

[28] E. Vandecandelaere, F. Arfini, G. Belletti & A. Marescotti (2010). Linking people, places and products. A guide for promoting quality linked to geographical origin and sustainable geographical indications, FAO publication.

[29] Ibid at 161

[30] Damary P et al (2017) TRAINING MANUAL on Linking people for quality products: Sustainable interprofessional bodies for geographical indications and origin-linked products